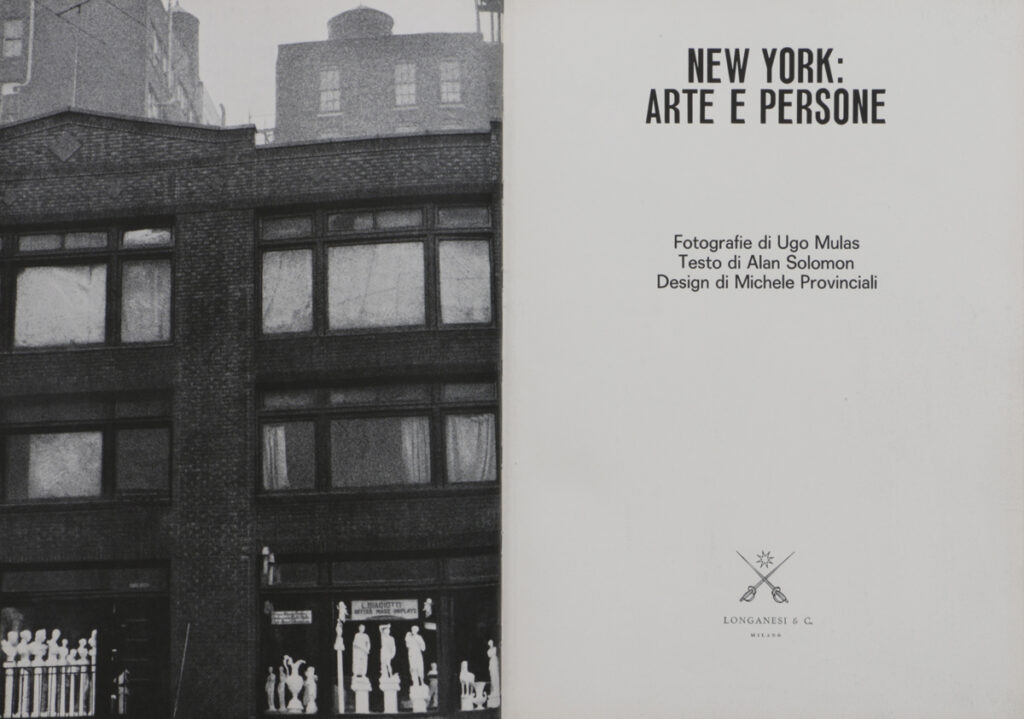

NEW YORK: THE NEW ART SCENE 1967

ALAN SOLOMON – INTRODUCTION

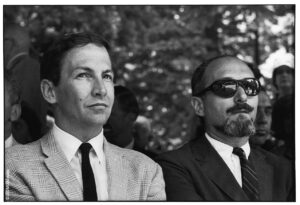

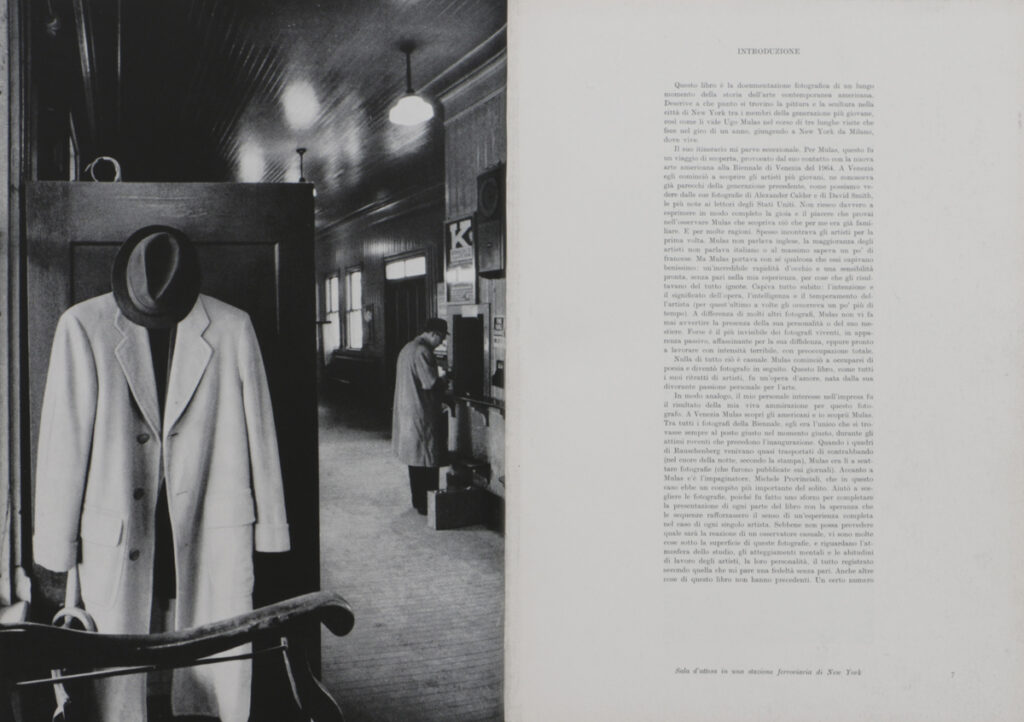

This book is a photographic record of a long moment in the history of contemporary American art. It is a record of the state of painting and sculpture in New York City among the members of the younger generation as they were seen by Ugo Mulas in the course of three extended visits within one year to New York from Milan, where he lives. As an observer on many occasions, I found it an extraordinary itinerary. For Mulas, it was a voyage of discovery, stimulated by his contact with the New American art during the Venice Biennale of 1964. There he began to discover the younger artists; he already knew a lot about the older generation, as we can see from his photographs Alexander Calder and David Smit, perhaps the best known of his work to readers in the United States. I cannot really convey my own pleasure and excitement at watching Mulas discover what was already familiar to me. For a number of reasons. In most cases he met the artists for the first time. He spoke no English, most of them spoke no Italian or a little French. But he brought something they understood: an uncanny quickness of eye and a trenchant sensibility, unequaled in my experience, to things that were absolutely unfamiliar to him. He understood everything at once, the intention of the artists, the meaning of the work, the mind and temperament of the artists (once in a while the latter took a little more time). Unlike many other photographers, he never makes you feel the presence of his own temperament or his craft. He may be the most invisible living photographer, seemingly passive, charming in a diffident way, yet working with a terrible intensity, with total preoccupation. None of this is any accident. Mulas started as a poet, and turned to photography rather late in life. This book, like all of his pictures of artists, was a work of love, coming out of his consuming personal passion for art.

In a similar way, my own involvement in the enterprise was the result of my consuming admiration for the photographer. If he discovered the American in Venice, I discovered him there. Of all the photographers covering the Biennale, he was the one who was always in the right place at the right time during the exciting events before the opening.

When Rauschenberg’s paintings were presumably being smuggled about in the dark of night, he was there taking photos (which appeared in all the magazines).

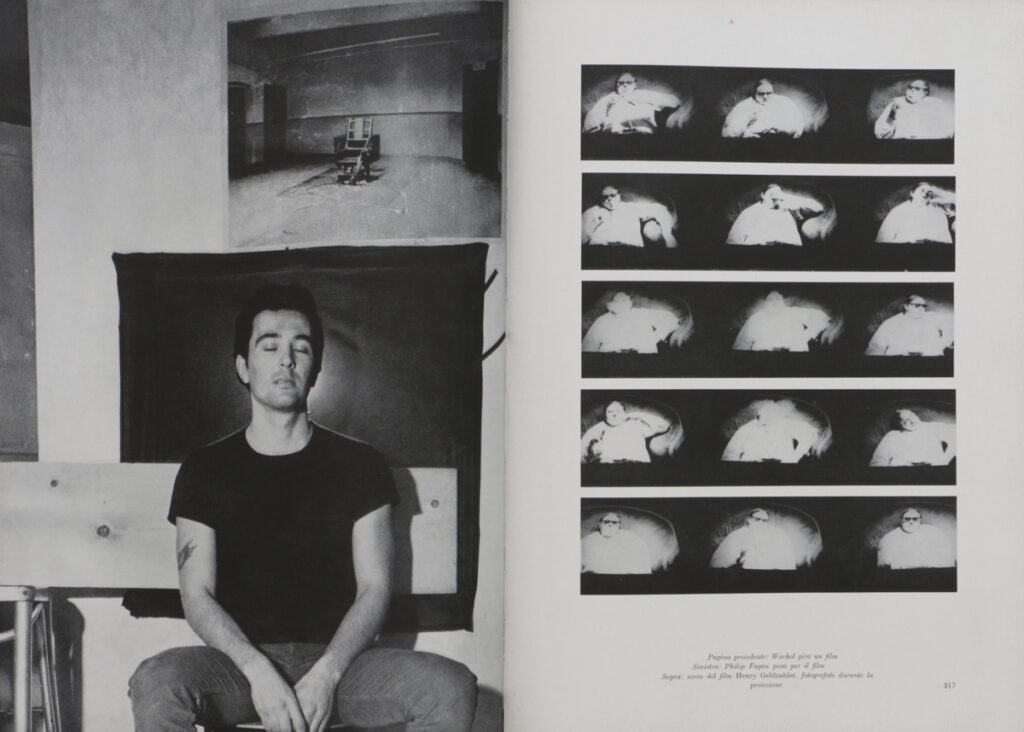

The team included on a more important member, the designer of the book, Michele Provinciali, who played a more involved role than is usually the case for a book designer. He helped to select the photographs, because an effort was made to integrate the presentation of each section of the book in a way which is not always possible. These pictures were taken for this book, and it was our hope that the sequences would reinforce the sense of a whole experience in the case of each artist.

Although i cannot tell how much the casual viewer sees of it, there is much in these pictures beneath the surface, about the mood of the studio, about the attitudes of mind and the work habits the artists bring there, about their own personalities, all recorded with what to me is unparalleled fidelity. Several other things about the book are without precedent. A number of artists, like Jasper Johns and Kenneth Noland, never before let photographers watch them work; these are original records of their studio activity. In many more than a few cases, the artists insisted that they had never before experienced such rapport with a photographer.

I believe something of this shows in the pictures, and I hope it makes them a special kind of record.

We owe our deepest thanks to the artists for their cooperation. In some cases, artists were photographed but the pictures could not be included, for various technical reasons; our apologies and regrets to them. The list of people included is nor meant to be exclusive. We did not include the older established painters; they have already been documented by others. We did not include many younger artists whose promise and accomplishment are already clear; we arbitrarily limited ourselves to those with established reputations. Most important of all, the people included interested the photographer.

Then, our friend Nancy Fish. One could say she translated, but this would not describe things like the way her imitation of Anna Magnani stopped traffic one rainy night on Ninth Avenue