- HOMAGE TO NIEPCE 1968-1970

The photograph I called Homage to Niépce is the result of a re-examination of my work as a photographer that I carried out a few years ago. I had begun to read books on the history

of photography, especially about its origins, certain reflections, certain writings by Niépce, Fox Talbot, Daguerre, and others. In these writings what stood out the most was the amazement at having at last found a way of separating the human hand from the creative process. It is a utopia; but the opposite is true as well, that is, it is also true that there is a power on the sensitive surface that goes beyond the human hand. From this point of view, you find yourself coming to terms not only with the objective reality, with the world, but also with the surface that is so

significant that it takes you where, at times, you would rather not go. In other words, you are forced to accept the reality. Walter Benjamin, in comparing the photograph to portrait panting, wrote: “With photography, however, we encounter something new and

strange; in Hill’s Newhaven fishwife, her eyes cast down in such indolent, seductive modesty, there remains

something that goes beyond testimony to the photographer’s art, something that cannot be silenced, that fills you with an unruly desire to know what her name was, the woman who was alive there, who even now is still real and will never consent to be wholly absorbed in art.”

As I thought about all this, I found myself coming to terms with my own work as well, a type of work that I began by chance. I was never even an amateur photographer: the first photo I took I sold right away. I was a student, hanging around almost always in that sort of café that was the Jamaica at the time, a latteria, or dairy store) where painters gathered. Someone lent me an old camera and said: “One one hundredth and eleven in the sun, one twenty-fifth five six in the shade.” And I, with great diffidence, took that camera in my hands. At first, the most exciting thing was the lab; I glimpsed the possibility of saving a photograph that had been poorly taken thanks to some process conducted in the darkroom, that is, using a particular type of paper, a certain cut. Then I realized just how important the lab is, because the image you create with your camera is not complete if it isn’t printed by you, or based on very precise indications that you have provided; but the lab could not be a panacea for all the problems with the shot, that its purpose was not to rescue negatives that came out wrong, but only to bestow on a good negative all of its value. Instead, the lab is important if we use it for what it is in itself, that is, if we eliminate the lens, and work directly on the surfaces, whether paper or film, the way Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy did, along with many others, with the precise intent of using what takes place in the lab as an independent fact, as a means to achieving an image that is purer and as direct as possible.

I remember how happy it made me to see my first successful photographs: I discovered in those images things I had not predicted, and that came into being precisely by virtue of the mechanism, the camera, the lens, the chemistry. And this empowered me. After a while you can forget how much you owe the camera; you feel as though you’re the one responsible for everything that happens, and you end up asking the camera to convey to you all of its power without worrying about the purpose, as long as it guarantees your success. You thus end up attributing to yourself a power that is nothing other than an extra force, one that you just happened to find yourself holding in your hands.

Around 1958 one book meant a lot to me: The Americans by Robert Frank. In those years I was interested in another type of photographic literature: the great photographers seemed to me to be the ones closest to the dangerous game of power I mentioned before. Instead in Frank’s book I could see for the first time a photographer who didn’t use any tricks, who took pictures that resembled those of an amateur, that is how technically simple they were. It took me a few years to understand this, because in the meantime I was distracted by my professional work, by my needs, by lots of things. Until I finally understood the meaning of Frank’s work: his not taking advantage, for the purpose of confusing this game of reality, of things, of life. The fact that the camera works on life directly, using people’s skin. Frank’s technical photographic discourse is the simplest of all: he uses a small camera, and an angular field wide enough not to emphasise the detail.

Many times I looked at Klein’s book about New York as an opposite solution. There you can sense that the photographer would have liked to go everywhere, to be more inside things with his hands, his ideology, that reality as it was was not enough, and so he cut, enlarged, burned, intervened as much as he could on the negative. I ask myself why, if a thing is already in itself shouted out, why would you need to add another shout; if a thing is already photographic, why you need to add another photographic element?

Then, in 1964, I went to America for a few months. It was something I personally felt the need to do, because no one had sent me there. I felt the need to go there after visiting the Venice Biennale: Johns, Dine, Oldenburg, Rauschenberg, Stella, Chamberlain were all there. At first, in the United States I was more dazed than convinced.

Then I became enthusiastic, because it was not so much a question of coming into contact with a certain type of painting, as one of entering the world of the painters, and at the same time sharing an extraordinary moment, being witness to something that was truly important just as it was unfolding and being affirmed. I had already photographed the artists, for instance Severini, Carrà likewise, but I had the feeling I was photographing survivors. I would have liked to photograph them in 1910, in 1912: it would have made sense then, while now all I was doing was recording their physical survival as major figures.

From my American experience a book was born, and if the photographs in that book mean anything, it was precisely in the fact of my taking part which I feared at the time, because I was conscious of a risk, because I knew of the allure of the people I was meeting, and that what was happening might betray me. For this reason, to escape this danger in part, I almost always used the same lens; not to distort face or objects as was the fashion in those years, but to remain as much as possible on the outside, distant, detached from what was happening, and also involve as many things as possible, as much space as possible, not isolating the protagonists but totally immersing them in their element. As I was taking pictures in New York and looking around, in Jim Dine’s house I was surprised to find a small framed photograph where you could see the interior of a room, probably in a hotel, with a TV on and the smiling face of a woman presenting some show. The room is empty, there is no presence other than the one mediated by the television. I continued with my work, but every now and again my mind wandered back to that photograph; I thought about the meaning of what I was doing, about whether that photograph actually made any sense. It was a photo by Friedlander, who was a complete unknown at the time – at least in Europe, where he continues to be unknown – because he was a photographer who rejected the mainstream channels of mass consumption, or perhaps those channels rejected him. Later, around 1968, I happened to come across some of Jim Dine’s print portfolios containing pictures taken by Friedlander, with a selection of about a dozen very specific photos, which open up new discussions. I believe there has never been a photographer as aware of what the photographic process involves, of how the photographer is him- or herself inside that process, in the camera or in the process, even physically so, and how this endows the photograph with all the ambiguities that accompany the first-person considerations. Between the photographer and the object the camera comes to life, it is a bulwark, but it is no longer the convenient bulwark against the neutrality of the photographer, nor is it an obstacle to his desire to intervene. What astonished me at the time was realising how the photographer lets himself be led by the camera, and vice versa, how the camera carries the photographer with truly unusual ease.

During my stay in America I had a chance to meet Robert Frank and we discussed all this. I explained to him that in my case I wanted to be impersonal, that I wanted to be someone who arrived on the scene and let the camera do the recording. Frank didn’t agree, he said you had to participate, be responsible, run the risk not only of making a mistake, but also of intervening and judging. I wanted to be a witness, I wanted to accept as many things as possible, but I couldn’t explain it. Clearly inside me there was either preparation or a lack of the same, there was a story, by which I mean that in the end, whether I intended to make it so or otherwise, my point of view came out in the photograph. But I didn’t know that being aware of this fact also meant having a different attitude at the time the picture was being taken, at the time the decision was made to photograph something and how it should be done.

Today I recognise that the pictures I took in America are a real awareness and not a recording, the same awareness that you can find in any authentic cognitive action.

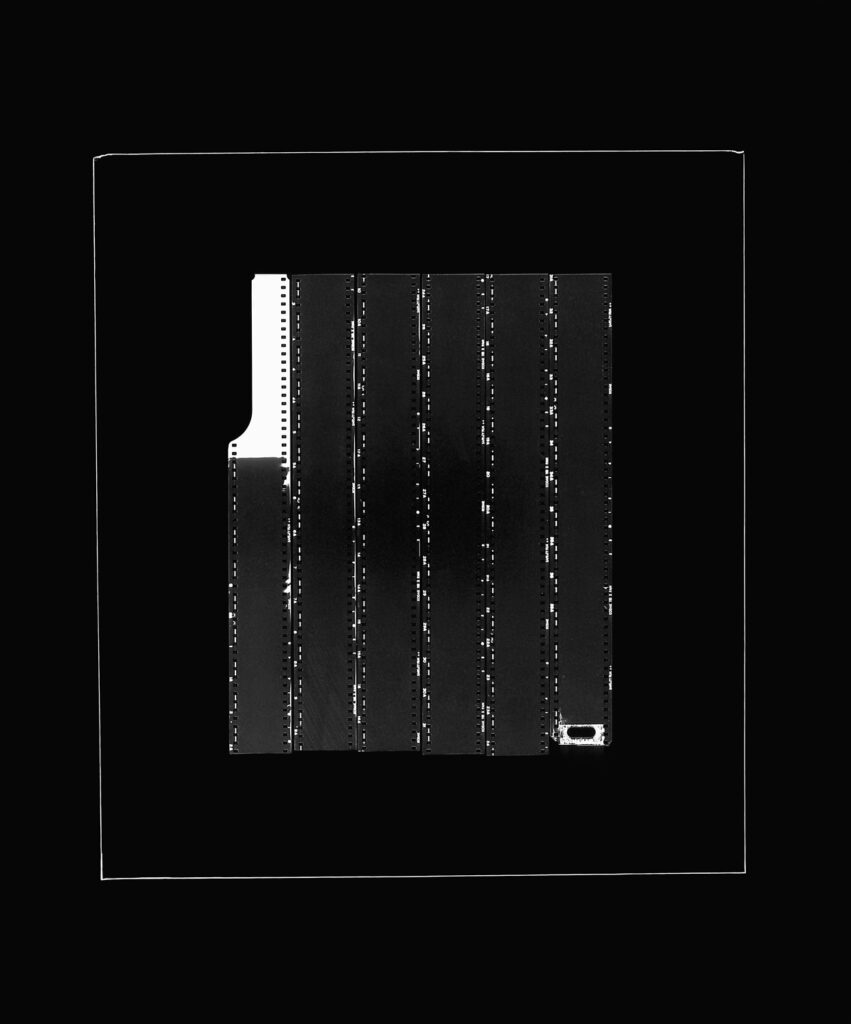

So, at a certain point, I began to use processes that were separate from those of others, separate from my desire to be a witness and to gather other people’s experiences, to see what this feeling of being alone vis-à-vis making something is, what it means no longer to seek props, no longer to seek truth in others, but instead to find it in ourselves, and to understand what the nature of this work is, to analyse each of its operations, to dismantle it as you might a camera, to become acquainted with it. Hence, this photograph, this object was born, the first in a series of verifications, after much hesitation, because I feared that the operation was too cerebral. I dedicated this first work to Niépce, because the first thing I found myself coming to terms with was the film roll, the sensitive surface, the key element of my entire trade, which is also the nucleus around which Niépce’s invention took shape. It is a verification, that is first of all a homage, a gesture of gratitude, a rendering unto Niépce what belongs to Niépce. For once the means, the sensitive surface, is the protagonist; it represents nothing other than itself.

We find ourselves before an unexposed roll of film that has been developed; the small piece that remained outside the cartridge was exposed to the light independently of my will, because it is the small piece that is always exposed to the light when you have to load the film into the camera: it is a pure photographic fact.

Even before the photographer begins any part of the process, something has already happened. Besides this small piece that is exposed to the light at the beginning, I also wanted to save the final part, the one that fastens the film to the spool. It is a small piece that you never use, that is never exposed, that you throw out, but that is still of fundamental importance. It is the point where a photographic sequence ends. Emphasising this piece means once again emphasising the moment when you take the film roll out of the camera to take it to the lab. It means finishing the work. This, too, is a photographic presence because, since there is still some glue stuck there, the light can’t pass through it. The film is printed in contact: the sheet of sensitive paper is placed underneath the enlarger, the negative cut into strips is arranged on the sheet, and placed on top of that is a rather heavy sheet of glass that keeps the strips pressed down, as flat as possible, so that the individual photograms appear neat, well-defined. Usually, a very small sheet is used, but I wanted to accentuate the glass, too. The glass frames the image, and it cannot be exchanged for a graphic element added to frame the photograph: without the glass there would not be that specific image, and what I like to consider is how, depending on the way the glass was cut, the outline surrounding the image thins accordingly. You can see that it wasn’t made by hand to produce a frame; it, too, is an element of the photograph.

I might add that this homage to Niépce represents thirty-six lost opportunities, thirty-six rejected opportunities, at a time when, as Robert Frank remarked in a comment about photojournalism, the air had become infected by the stench of photography.